Better predicting a patient’s response to cancer treatment

SCIENTIFIC EVIDENCE SUGGESTS THAT INTRODUCING CHEMOTHERAPY BEFORE IMMUNOTHERAPY — OR DOING BOTH AT THE SAME TIME — CAN ALTER THE MICROENVIRONMENT, IMPROVING THE ODDS OF SUCCESSFUL TREATMENT.

Every tumor adapts to its unique place of growth within the body. These changes create complex ecosystems, each made up of different kinds of cells. The interactions within these microenvironments can be analyzed to determine how cancer progresses and how it is affected by anti-cancer treatments. A deeper understanding of these processes will shed light on how two common forms of cancer treatment — immunotherapy and chemotherapy — might best be used in concert to improve health outcomes for cancer patients. The need for that better understanding is why the FNIH launched a project called Chemotherapeutic Impact on the Immune Microenvironment, or ChIIME.

The fastest-growing type of cancer treatment is immunotherapy, which stimulates the body’s natural immune system to attack cancer cells. It has shown great success for some kinds of cancers and some patients, but not all. Scientific evidence suggests that introducing chemotherapy before immunotherapy — or doing both at the same time — can alter the microenvironment, improving the odds of successful treatment.

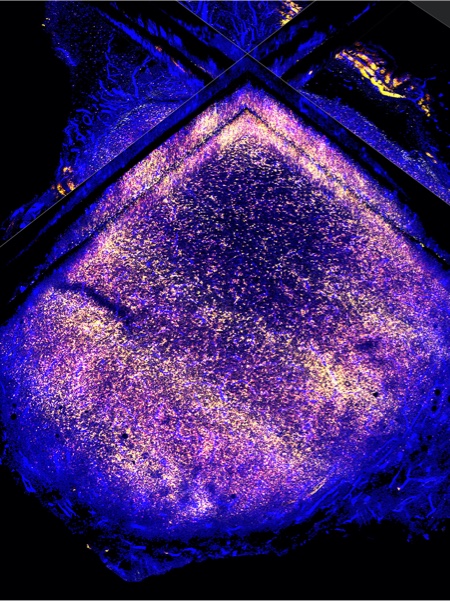

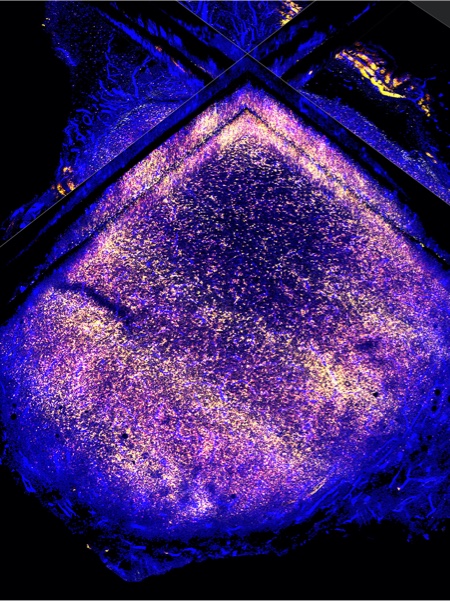

Led by experts from the FNIH, the National Cancer Institute (NCI), the FDA, academia and industry, the ChIIME project uses a cutting-edge technology called single nucleus RNA sequencing to analyze the microenvironment of breast cancers that are particularly resistant to most therapies. The analysis technique allows for a clearer picture of all cell populations in the microenvironment, interactions among different cells and features that explain tumor cells’ responses to treatment. Studying breast cancer samples in this way, scientists will learn more about the effects of chemotherapy on different kinds of cells, including immune cells.

Ultimately, the insights gleaned from this investigation will be used to develop biomarkers that inform therapeutic decisionmaking. The knowledge will help to guide the ways that therapies are designed and assigned to patients, potentially leading to new and better treatment options for people with cancer.